Roundabout is a good starting point to your desire «to make mechanic driven games with original themes». Why this focus on mechanics and original themes? What were you missing on other games?

Roundabout is a good starting point to your desire «to make mechanic driven games with original themes». Why this focus on mechanics and original themes? What were you missing on other games? I think a lot of why we’re a mechanic focused studio comes from our upbringing – both Panzer and I grew in the industry as mechanic-focused designers. They’re also incredibly fun and rewarding to make compared to narrative-focused games, since you’re spending all your time making replayable systems more fun instead of years on content that people will only look at once.

Unfortunately, the number of game studios making these kinds of games seems to be shrinking over time. Founding No Goblin was part of us trying to rectify that by making the kinds of games we felt were missing in the world.

You also talked about your games having «no half-hour ‘interactive cinematics’» when you introduced No Goblin. I wasn’t expecting the kind of video you use in Roundabout. How did you come up with this idea? A lot of the inspiration for the FMV in Roundabout comes from working at Twisted Pixel on games like The Gunstringer. While I’ll probably never be as accomplished a screenwriter or director as Josh Bear, I was still bitten by the bug of filming our friends doing goofy things on camera to make our game better.

As a small developer, recording FMV has really helped us convey emotion and narrative in a way that would be financially out of reach to us otherwise. It also means we now own a company skeleton, and anything that results in explaining why we own a skeleton to our accountant can’t be all bad.

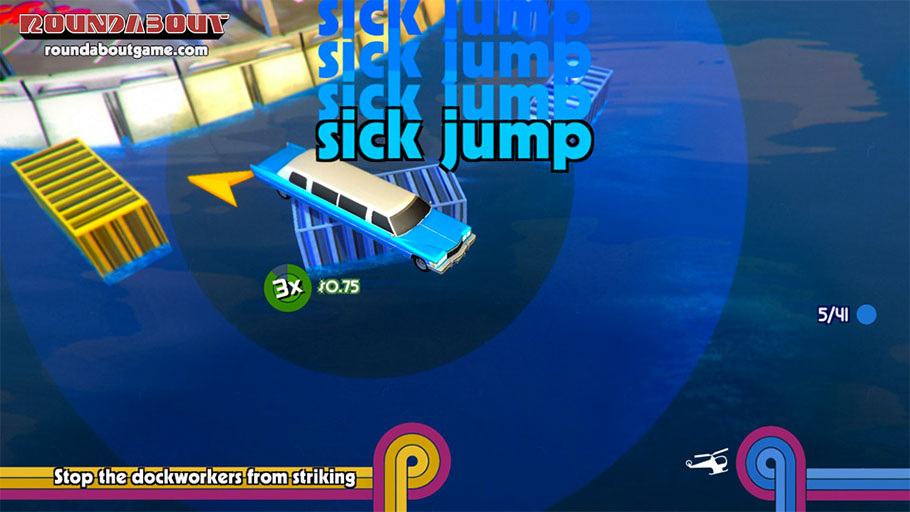

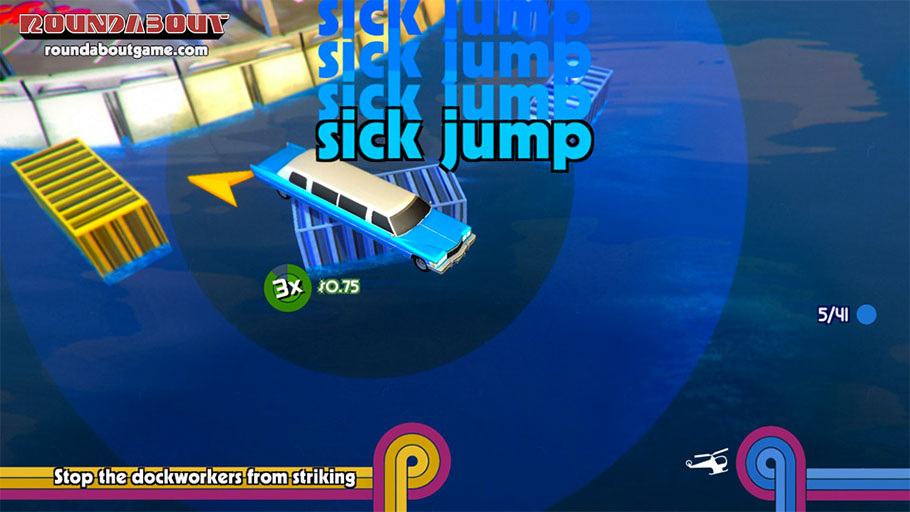

The whole game seems like a really crazy idea —I like to think about it as a «GTA 2 meets Kuru Kuru Kururin» kind of game. What kind of games influenced Roundabout? There’s definitely a Kururin inspiration behind the whole “revolving limousine” thing, but past that point we’ve ended up pulling from a pretty wide range of sources. Our scoring system is inspired by Tony Hawk, our Challenge mode by Trials HD, we even have a dedicated speed run mode and leaderboard that’s inspired by all of the crazy runs from events like All Games Done Quick.

You’re not new to craziness. Ms. Splosion Man or Destroy All Humans! also featured this crazy sense of humor and setting. How do you think comedy can help video games? Why do you like to use humor, when so many games usually go for a much more serious (and usually boring) themes? I enjoy playing and watching serious stuff, but I really don’t enjoy making it. The whole point of life is to be happy, right? I’m much happier making things that people laugh with and enjoy than I am scaring people or making people cry.

As an ex-Rock Band, ex-Splosion Man guy, how has been forming a new studio? How big (or small!) are you, and how has this affected your development habits?

As an ex-Rock Band, ex-Splosion Man guy, how has been forming a new studio? How big (or small!) are you, and how has this affected your development habits? We’re starting out small – full time it’s just Panzer and I, and we’ve enlisted my YouTube sensation brother

Beagle to be our FMV editor. It’s pretty great having nobody between a crazy idea and full implementation, but it’s also ridiculously scary that there’s no safety net of other people to pick up tasks.

It’s also given me a new appreciation for all of the logistics and business things you need to do to get a game out the door! I have no idea how so many game CEOs look so healthy after dealing with this kind of stuff for years at a time!

As indie games become more and more popular, a lot of devs are going solo or forming their own studios. Twisted Pixel wasn’t a huge studio. Why did you decide to create No Goblin? Leaving Twisted Pixel was a really hard call, especially since they have an amazing team and I loved working there. Having said that, starting a studio has been a long time dream of mine. When everything lined up perfectly to do that last year, it was impossible to say no.

As a developer who has been in both sides, how should be the ideal (or an ideal) relationship between triple A, kinda industrial-made games and smaller, independent games, more suited to deliver personal stories and messages? I think labels like “AAA” and “Indie” don’t really serve that much use. Even when I was working on 300-person AAA games, everyone on that team loved what they were making and saw it as part of something they were personally making for people to enjoy. It’s the same feeling I get with two people on Roundabout, the only difference is the scale of what we’re making.

Roundabout is a good starting point to your desire «to make mechanic driven games with original themes». Why this focus on mechanics and original themes? What were you missing on other games? I think a lot of why we’re a mechanic focused studio comes from our upbringing – both Panzer and I grew in the industry as mechanic-focused designers. They’re also incredibly fun and rewarding to make compared to narrative-focused games, since you’re spending all your time making replayable systems more fun instead of years on content that people will only look at once.

Unfortunately, the number of game studios making these kinds of games seems to be shrinking over time. Founding No Goblin was part of us trying to rectify that by making the kinds of games we felt were missing in the world. You also talked about your games having «no half-hour ‘interactive cinematics’» when you introduced No Goblin. I wasn’t expecting the kind of video you use in Roundabout. How did you come up with this idea? A lot of the inspiration for the FMV in Roundabout comes from working at Twisted Pixel on games like The Gunstringer. While I’ll probably never be as accomplished a screenwriter or director as Josh Bear, I was still bitten by the bug of filming our friends doing goofy things on camera to make our game better.

As a small developer, recording FMV has really helped us convey emotion and narrative in a way that would be financially out of reach to us otherwise. It also means we now own a company skeleton, and anything that results in explaining why we own a skeleton to our accountant can’t be all bad. The whole game seems like a really crazy idea —I like to think about it as a «GTA 2 meets Kuru Kuru Kururin» kind of game. What kind of games influenced Roundabout? There’s definitely a Kururin inspiration behind the whole “revolving limousine” thing, but past that point we’ve ended up pulling from a pretty wide range of sources. Our scoring system is inspired by Tony Hawk, our Challenge mode by Trials HD, we even have a dedicated speed run mode and leaderboard that’s inspired by all of the crazy runs from events like All Games Done Quick. You’re not new to craziness. Ms. Splosion Man or Destroy All Humans! also featured this crazy sense of humor and setting. How do you think comedy can help video games? Why do you like to use humor, when so many games usually go for a much more serious (and usually boring) themes? I enjoy playing and watching serious stuff, but I really don’t enjoy making it. The whole point of life is to be happy, right? I’m much happier making things that people laugh with and enjoy than I am scaring people or making people cry.

Roundabout is a good starting point to your desire «to make mechanic driven games with original themes». Why this focus on mechanics and original themes? What were you missing on other games? I think a lot of why we’re a mechanic focused studio comes from our upbringing – both Panzer and I grew in the industry as mechanic-focused designers. They’re also incredibly fun and rewarding to make compared to narrative-focused games, since you’re spending all your time making replayable systems more fun instead of years on content that people will only look at once.

Unfortunately, the number of game studios making these kinds of games seems to be shrinking over time. Founding No Goblin was part of us trying to rectify that by making the kinds of games we felt were missing in the world. You also talked about your games having «no half-hour ‘interactive cinematics’» when you introduced No Goblin. I wasn’t expecting the kind of video you use in Roundabout. How did you come up with this idea? A lot of the inspiration for the FMV in Roundabout comes from working at Twisted Pixel on games like The Gunstringer. While I’ll probably never be as accomplished a screenwriter or director as Josh Bear, I was still bitten by the bug of filming our friends doing goofy things on camera to make our game better.

As a small developer, recording FMV has really helped us convey emotion and narrative in a way that would be financially out of reach to us otherwise. It also means we now own a company skeleton, and anything that results in explaining why we own a skeleton to our accountant can’t be all bad. The whole game seems like a really crazy idea —I like to think about it as a «GTA 2 meets Kuru Kuru Kururin» kind of game. What kind of games influenced Roundabout? There’s definitely a Kururin inspiration behind the whole “revolving limousine” thing, but past that point we’ve ended up pulling from a pretty wide range of sources. Our scoring system is inspired by Tony Hawk, our Challenge mode by Trials HD, we even have a dedicated speed run mode and leaderboard that’s inspired by all of the crazy runs from events like All Games Done Quick. You’re not new to craziness. Ms. Splosion Man or Destroy All Humans! also featured this crazy sense of humor and setting. How do you think comedy can help video games? Why do you like to use humor, when so many games usually go for a much more serious (and usually boring) themes? I enjoy playing and watching serious stuff, but I really don’t enjoy making it. The whole point of life is to be happy, right? I’m much happier making things that people laugh with and enjoy than I am scaring people or making people cry.  As an ex-Rock Band, ex-Splosion Man guy, how has been forming a new studio? How big (or small!) are you, and how has this affected your development habits? We’re starting out small – full time it’s just Panzer and I, and we’ve enlisted my YouTube sensation brother Beagle to be our FMV editor. It’s pretty great having nobody between a crazy idea and full implementation, but it’s also ridiculously scary that there’s no safety net of other people to pick up tasks.

It’s also given me a new appreciation for all of the logistics and business things you need to do to get a game out the door! I have no idea how so many game CEOs look so healthy after dealing with this kind of stuff for years at a time! As indie games become more and more popular, a lot of devs are going solo or forming their own studios. Twisted Pixel wasn’t a huge studio. Why did you decide to create No Goblin? Leaving Twisted Pixel was a really hard call, especially since they have an amazing team and I loved working there. Having said that, starting a studio has been a long time dream of mine. When everything lined up perfectly to do that last year, it was impossible to say no. As a developer who has been in both sides, how should be the ideal (or an ideal) relationship between triple A, kinda industrial-made games and smaller, independent games, more suited to deliver personal stories and messages? I think labels like “AAA” and “Indie” don’t really serve that much use. Even when I was working on 300-person AAA games, everyone on that team loved what they were making and saw it as part of something they were personally making for people to enjoy. It’s the same feeling I get with two people on Roundabout, the only difference is the scale of what we’re making.

As an ex-Rock Band, ex-Splosion Man guy, how has been forming a new studio? How big (or small!) are you, and how has this affected your development habits? We’re starting out small – full time it’s just Panzer and I, and we’ve enlisted my YouTube sensation brother Beagle to be our FMV editor. It’s pretty great having nobody between a crazy idea and full implementation, but it’s also ridiculously scary that there’s no safety net of other people to pick up tasks.

It’s also given me a new appreciation for all of the logistics and business things you need to do to get a game out the door! I have no idea how so many game CEOs look so healthy after dealing with this kind of stuff for years at a time! As indie games become more and more popular, a lot of devs are going solo or forming their own studios. Twisted Pixel wasn’t a huge studio. Why did you decide to create No Goblin? Leaving Twisted Pixel was a really hard call, especially since they have an amazing team and I loved working there. Having said that, starting a studio has been a long time dream of mine. When everything lined up perfectly to do that last year, it was impossible to say no. As a developer who has been in both sides, how should be the ideal (or an ideal) relationship between triple A, kinda industrial-made games and smaller, independent games, more suited to deliver personal stories and messages? I think labels like “AAA” and “Indie” don’t really serve that much use. Even when I was working on 300-person AAA games, everyone on that team loved what they were making and saw it as part of something they were personally making for people to enjoy. It’s the same feeling I get with two people on Roundabout, the only difference is the scale of what we’re making.

Solo los usuarios registrados pueden comentar - Inicia sesión con tu perfil.